Choose a Gallery:

Exhibit Home | The Secret War | A New Home | Religion & Traditional Ceremonies | Traditional Arts

"We lose people, we lose everything, we lose the country by the war.” — Neng Vang Lor, 2009

Who are the Hmong? | Hmoob Yog Leej Twg?

The Hmong do not have their own nation state, and trace their ancestry back to China’s southern provinces. Hmong people began migrating south in the early 1800s, fleeing conflict with the Chinese dynasty. Most Hmong settled in the highlands of northern Laos, establishing small villages and practicing slash-and-burn agriculture.

Raw li keeb kwm qhia tseg mas Hmoob yog los Suav teb los. Txij li thaum 1800 ces Hmoob pib khiav tawm hauv Suav teb vim yog kev ua tsov rog nrog neeg Suav. Thaum 1800 yuav tas Hmoob feem coob tau los nyob rau sab qaum teb hauv teb chaws Nplog. Lawv los sib sau ua vaj ua tsev nyob rau tej toj roob hauv pes, luaj teb ntov ntoo ua noj ua haus nyob rau hauv Nplog teb.

The Secret War | Tsov Rog Nyob Nplog Teb

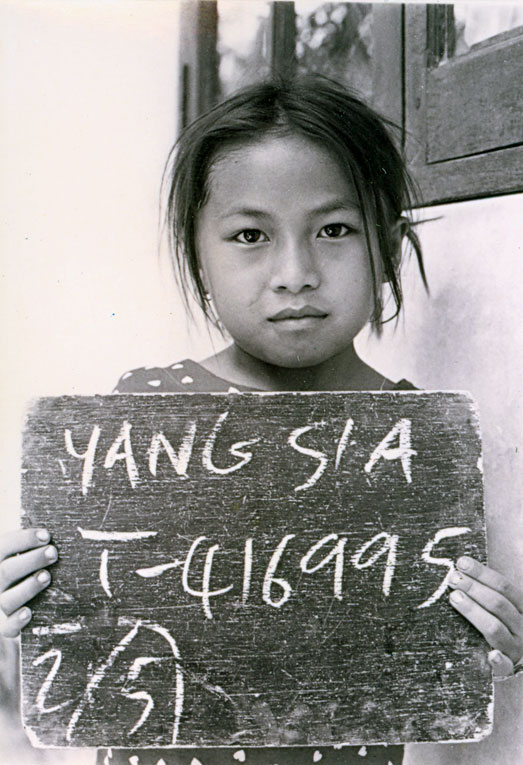

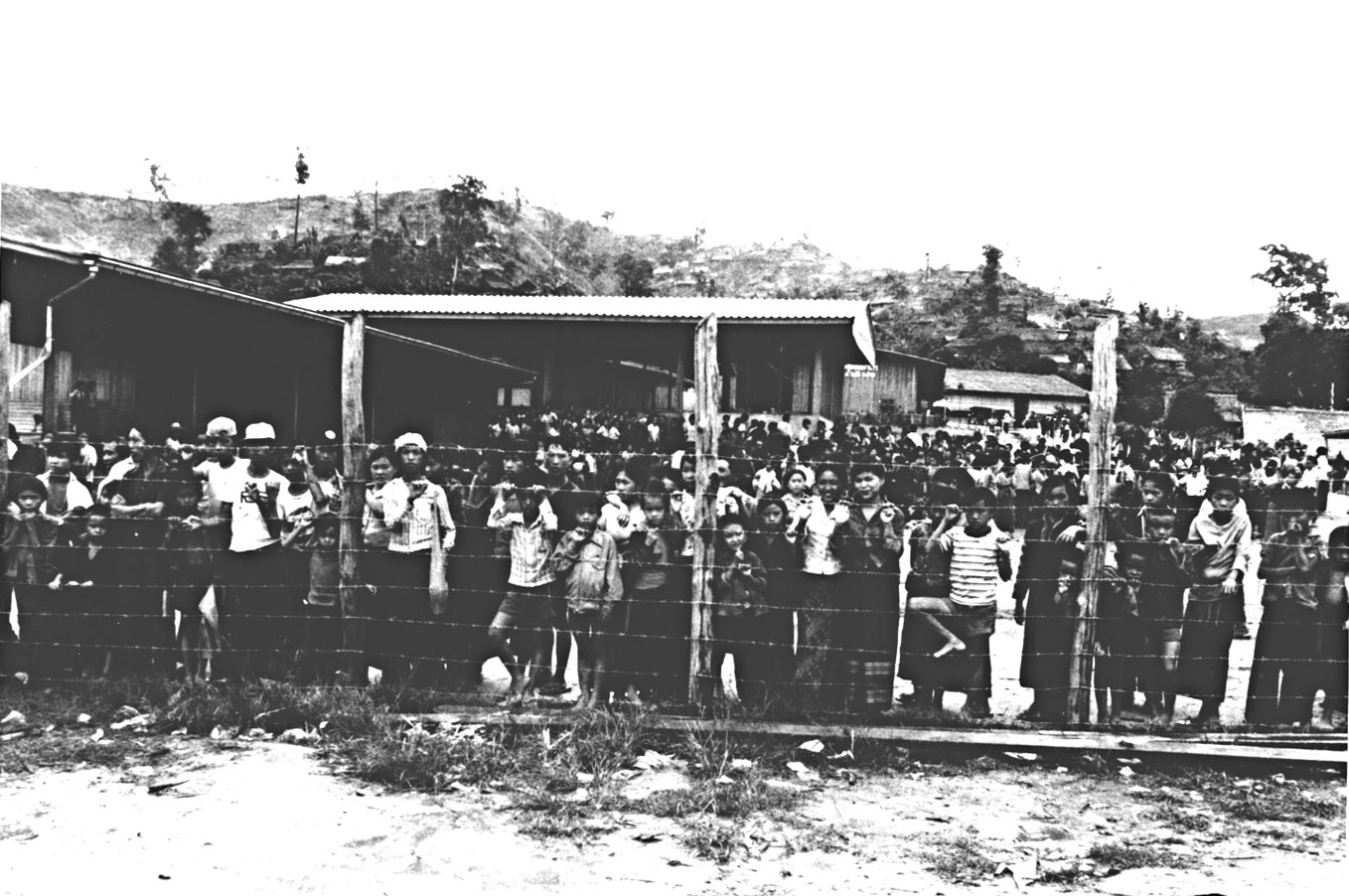

Laos gained its independence from France in 1954 and the Geneva Accords established it as a neutral nation. From 1961 to 1975, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency actively recruited Hmong men and boys to fight a secret war in Laos in direct violation of the Geneva Accords. Hmong soldiers under General Vang Pao blocked supplies headed for South Vietnam and served as the primary anti-communist force in Laos during the Vietnam War. When American forces withdrew from Southeast Asia in 1975, thousands fled to Thailand as refugees.

Lub teb chaws Nplog tau txais kev muaj vaj huam sib luag/kev ywj pheej los ua ib lub teb chaws los ntawm Fab Kis xyoo 1954 uas yog ib lub teb chaws lawv txwv tsis pub ua tsov rog nrog lwm lub teb chaws—nov yog txoj cai tsim los hauv Geneva Accords. Txij li xyoo 1961 mus txog xyoo 1975, Asmeskas (CIA) tau tuaj ntxias Hmoob kom cov txiv neej thiab me nyuam tub mus ua rog pab Asmekas tua nyaj laj qaum teb yam tsis pub ntiaj teb paub ces qho nov yog ib qho yuam cai hauv Geneva Accords. Hmoob tej tub rog nrog rau Nais Phoo Vaj Pov tau tiv thaiv nyab laj qaum teb kom lawv txhob xa tau tej cuab yeej khoom siv ua tsov rog tuaj mus rau nyab laj qab teb lub sij hawm nyab laj qaum teb thiab nyaj laj qab teb ua tsov ua rog.

“So, when the war was over and the American CIA was withdrawn from Laos, the communists took over and they said we, the Hmong people, were the hands, eyes, and ears of the American CIA. And they killed mostly men … and young boys…. It was very difficult for us to live in there. After 1975, we moved to the jungle to hide.… We had fought until 1978 without anyone’s support.… We fought communists.… We lost our village, and my family with other families, about 3,000 people, walked and fought our way to Thailand. It took us about two and a half months to get to the Mekong River.… When we crossed the Mekong River, we used bamboo for floating.” — Joe Bee Xiong, 1992

Exhibit Home | The Secret War | A New Home | Religion & Traditional Ceremonies | Traditional Arts