Changing Currents Feature No. 2

Posted: July 31, 2014

"We Wish to Remain Here": Chief Buffalo and the Fight for Ojibwe Homelands

Our new exhibit Changing Currents: Reinventing the Chippewa Valley is now open for preview. Each month we are sharing one in-depth story from the exhibit, leading up to the official grand opening celebration December 7. Each article will introduce a different era of Chippewa Valley history, digging deeper into the story of a particular event, person, or theme. The story of Chief Buffalo comes from a section we call "Land of Strangers." In this section, visitors get to explore the interactions that took place among different groups of people when American and foreign-born settlers began arriving in the Chippewa Valley and when the U.S. government first became involved in regional affairs.

In the spring of 1852, Ojibwe chief Kechewaishke, also known as Chief Buffalo, led a small group of Ojibwe men and a local interpreter on a long journey to Washington, D.C., to take their grievances directly to the President of the United States. They were representatives of Ojibwe throughout Wisconsin, who believed that they continued to be under threat of forced removal west into Minnesota Territory. Chief Buffalo had been a respected Ojibwe leader for decades and was approximately 93 years old at the time he undertook the 1852 expedition.

The meeting of this revered elder with President Millard Fillmore stands as the iconic moment that eventually resulted in permanent reservations on Ojibwe homelands. However, the successful achievement of Chief Buffalo's goals took much more time and involved many more people than a single meeting with the President. Ojibwe leaders--Chief Buffalo foremost--should be remembered not just for the 1852 journey, but for what the journey represented at the time: patience, perseverance, and resilient leadership over many years.

Ojibwe Treaties with the United States

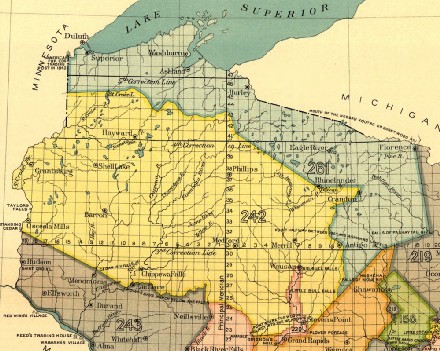

To understand the deeper meanings that underlay the 1852 trip to Washington, one must first understand how Ojibwe people interpreted the treaties they had signed with the U.S. government in the preceding decades. When Ojibwe leaders, including Chiefs Buffalo from La Pointe, Apishkaagaagi from Lac du Flambeau, and Bakwe'aamoo from Lac Courte Oreilles, signed the 1837 Treaty of St. Peters, they believed they were selling or leasing access to one particular resource--pine trees--within the boundaries established. The "Pine Treaty," as it is known informally, included nearly all of the Chippewa Valley north of what are now the cities of Eau Claire and Menomonie. In 1842, many of the same Ojibwe leaders were pressured into signing another treaty, known as the "Copper Treaty," offering the American government similar access to mineral resources in the territory bordering Lake Superior.

The Ojibwe had ceded rights to pine and copper. They had not ceded the land outright. Both treaties stipulated that the Ojibwe retained the rights to hunt, fish, gather wild rice, and produce maple sugar on all the ceded lands.

As early as 1842, Buffalo, head chief of the La Pointe band, led Ojibwe resistance to the way the treaty negotiations were conducted, to the provisions in the treaties themselves, and to the broader "land rights" interpretation of the treaties American officials had begun to use. Buffalo claimed Indian Agent Robert Stuart had not even let him speak at the 1842 negotiations because Stuart knew him to be opposed to the treaty. In an effort to be proactive, some of the warriors from Buffalo's band requested in 1843 that a secure reservation of land along the Bad River be guaranteed to the Ojibwe of La Pointe: "Our grand father [the President] bought our lands for the copper it contains. There is a piece of land where this metal is not found; the trees are not good (pine), & there is nothing there that the pale faces can make use of. We want our Grand father to reserve us this land, where we can make our sugar & plant our gardens."

Though the request was denied, the course of peaceful political action the Ojibwe used during the early 1840s-directed by the influential Chief Buffalo-remained the path Wisconsin's Ojibwe would follow for more than a decade in dealings with the United States government, even as their relationship with the U.S. became increasingly frustrating and painful.

This map shows the land discussed under the terms of the 1837 "Pine Treaty" (yellow) and the 1842 "Copper Treaty" (light blue). Also shown are townships and cities which were later surveyed and platted over the ceded lands. From a Bureau of American Ethnology map, online here.

Growing Fears and the Envoy of 1848

By the 1840s, the Lake Superior Ojibwe were well aware of the American government's efforts to remove and resettle the region's Indian nations to the west side of the Mississippi River. At the 1842 "Copper Treaty" negotiations, for example, Indian Agent Stuart explained to the Ojibwe chiefs, "As these lands may at some future day be required, your great Father does not wish to leave you without a home," and promised future reservations in what is now Minnesota. When Ojibwe like Buffalo asked him to be specific about when they would be asked to leave, he explained vaguely that the removal would not be for a very long time. Like earlier American representatives, Stuart led Ojibwe men and women to believe that they could live and eventually even die on their homelands as long as they remained peaceable. Only later generations would bear the burden of removal.

Only a few years later, however, the issue became urgent. In 1847, Chief Buffalo other Ojibwe leaders were signatories to a four-way agreement that ceded some Ojibwe and Dakota lands in what is now central Minnesota. The ceded land was set aside as reservations to be occupied by Menominee and Winnebago [Ho-Chunk] people, who were being forced out of Wisconsin. The implication of such treaties was clear. It would be only a short time before the U.S. government would attempt to do the same to the Ojibwe.

Departing northern Wisconsin in October 1848, not long after Wisconsin was admitted as a state and still four years before Chief Buffalo's more famous journey to Washington, a group of eight Lake Superior Ojibwe men travelled to the American capital city to meet with President James K. Polk. Oshkaabewis, a member of the Crane Clan who resided at Lac Vieux Desert and later Lac du Flambeau, led the envoy. Mixed-heritage interpreter John Baptiste Martell, two Ojibwe women, and the infant child of a Oshkaabewis and his wife Pammawaygeonenoqua also made the long, arduous journey from northern Wisconsin to Washington by way of St. Louis, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia. (The infant became sick and died in Philadelphia, leaving both parents grief stricken). Finally, Chief Buffalo's pipe carrier Blackbird, a high-ranking chief in his own right, went as far as Ohio before turning back.

The delegation finally met with President Polk in February 1849. Shortly after that meeting, they presented their petitions before the House of Representatives. The written petition, which made it into the Congressional record, stated "that our people . . . desire a donation of twenty-four sections of land, covering the graves of our fathers, our sugar orchards, and our rice lakes and rivers, at seven places now occupied by us as villages." It was a similar request to the one Chief Buffalo's band had made five years earlier. Since the Ojibwe envoy had been forced to dance and perform in stereotypical Indian fashion to raise money during the outbound journey, they also asked Congress for $6,000 to cover the expenses of returning home.

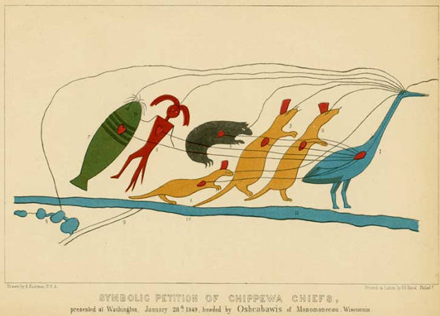

In addition to the written petition, the Ojibwe delegation presented several symbolic petitions. Drawn on birchbark, the symbolic petitions used clan totems of Ojibwe from different regions around Lake Superior to show the attachment they had to their homelands. The petitions demonstrated the Ojibwe's unity of mind in seeking reservations on their homelands. In the House of Representatives, one of the Ojibwe chiefs took the seat of the presiding officer, and according to a newspaper account of the interpreter's own words before Congress, asked only for justice, "which the grand council of a great nation such as yours should promptly accord to allies and dependents who . . . have generously given you lands which have contributed much to your national greatness."

The envoy of 1848-49 was received kindly. Congress awarded the $6,000 they requested, and President Polk approved of their conduct. Unfortunately, this attempt by Ojibwe leadership to preempt removal efforts--to proactively seek a compromise before the issue came to a head--could not have been presented at a worse time. Many of the American politicians who were so impressed by the Ojibwe cause were lame ducks, not least of which was President Polk, a Democrat. A new president and new Congress were sworn in only a few weeks after the Ojibwe departed for home, and with the new Whig leadership came a much harsher stance on the question of Ojibwe removal.

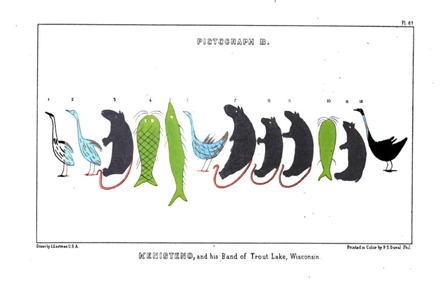

Seth Eastman famously painted copies of the symbolic petitions when he encountered the Ojibwe envoy on the Mississippi River. Henry Rowe Schoolcraft published the Eastman copies a few years later in a book about Indian cultures. Schoolcraft's book--including all of the pictographs--is available on Google Books. Begin on page 415.

The most famous pictograph (above) represents Oshkaabewis (the Crane), leader of the 1848-49 expedition. The second (below) represents "the Chippewas of Trout Lake, on the sources of the Chippewa River," according to Schoolcraft.

Removal Becomes Reality--the Sandy Lake Tragedy

"Tell him [Alexander Ramsey] I blame him for the children we have lost," wrote Ojibwe chief Aish-ke-bo-go-ko-zhe (Flat Mouth), in a December 3, 1850 letter directed to Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey. Ramsey was a Pennsylvanian appointed in 1849 to govern recently created Minnesota Territory by new Whig President Zachary Taylor. After Ramsey's actions in 1850, the Ojibwe had good reason to blame him and his colleague, Indian Subagent John Watrous, for a disastrous attempt to force Wisconsin Ojibwe permanently into Minnesota.

In exchange for the timber and mineral concessions they agreed to in the treaties, the Ojibwe received from the U.S. government annual payments of cash, food, and other goods to help support themselves as the fur trade economy evaporated. During the 1840s, these annuity payments were made at La Pointe on Madeline Island, a location that was both an important Ojibwe spiritual center and relatively accessible for Ojibwe throughout the region. The payouts became notable events for both good and bad reasons. Payments brought different bands together to renew ties. They provided an opportunity for Ojibwe leaders to meet with the government Indian Agent and to hold council about future collective actions. But annuity payments were also places where American traders swarmed, trying to collect as much of the government's cash as possible, often through dishonest means.

With support from President Taylor and Whig appointees at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, Governor Ramsey concocted a plan to move the site of the Ojibwe annuity payments to Sandy Lake, near Lake Mille Lacs in Minnesota Territory. He hoped traders in Minnesota rather than those in Wisconsin would be able to profit from the payments. President Taylor wrote an illegal executive order requiring all Wisconsin Ojibwe to leave the lands contained in the 1837 and 1842 treaties. With Taylor's executive order in hand, Ramsey and Watrous set the 1850 annuity payment for late autumn at Sandy Lake to prevent Ojibwe from Wisconsin and Michigan's Upper Peninsula from returning home. They believed winter would force the Ojibwe to remain at Sandy Lake.

Ojibwe leaders were in disbelief. Lacking a deep understanding of the fickle American political system, the Ojibwe saw this change of fortunes as a betrayal of the highest order. Considering the many assurances the 1848 envoy had been given, what had the Ojibwe done to cause the president to change the payment location and order them to remove? Some Ojibwe, including Buffalo, did not believe the order actually came from the president. Rather, they thought Watrous had made it up. Already mistrustful of Watrous and the removal order, Ojibwe men and women were reluctant to make the difficult trip so late in the season. On the other hand, not to go would mean forfeiting their right to a year's worth of goods and money.

Unfortunately, many Ojibwe families chose to make the journey to Sandy Lake that October. The government--at both federal and territorial levels--botched the 1850 annuity payment. The payment arrived six weeks later than scheduled and contained only a portion of the promised goods. In the meantime provisions ran out, and what food Subagent Watrous had provided was rotten. Several hundred Ojibwe men, women, and children died at Sandy Lake or while returning home over the now frozen ground in December and January. Though the government's failure to deliver the payment in full and on time seems to have been unintentional, the tragedy left permanent marks on Wisconsin's Ojibwe community.

The Path Not Taken

Benjamin Armstrong, Chief Buffalo's son-in-law and an interpreter for the 1852 delegation to Washington, recalled that after the Sandy Lake tragedy, the "turbulent spirit of the young warriors" was stoking "the fire that was smoldering into an open revolt for revenge." If there were a time for Ojibwe leaders to adopt a more forceful or violent political strategy in dealing with the U.S. government, this would have been it. Chief Buffalo and other Ojibwe chiefs spent 1851 searching far and wide for an explanation of the removal order, all the while keeping angry young warriors in check. Indian Subagent Watrous's announcement that the 1851 payment would again take place in Minnesota Territory could have been the moment the simmering anger boiled over.

Yet the peaceful, diplomatic approach again prevailed. This happened for a variety of reasons.

First, a silver lining of the Sandy Lake tragedy came in the form of media attention and white allies. Newspapers as far away as New York printed sympathetic accounts and editorials of how the Ojibwe had been "reduced to starvation by the shameful negligence of the Government" and decried the removal effort as "uncalled for." Leading white businessmen in the upper Great Lakes and the Wisconsin state legislature sent petitions to the president. (President Taylor died in 1850 after only a year in office, so President Millard Fillmore received the petitions.)

Second, and this is the point that has been overlooked in earlier accounts, Chief Buffalo continued to seek peaceful solutions. He knew that violence could only lead to the destruction of the Ojibwe people. By 1851, Chief Buffalo was an experienced politician in the American sense, a man who comprehended important elements of the American worldview and adjusted the Ojibwe position accordingly. During the crisis of 1851, he was the lead author of a scathing letter to the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington about the deceitfulness of Subagent Watrous and the deaths at Sandy Lake. "We wish . . . to remain here, where we were promised we might live," he concluded assertively. At the same time, he was a voice of calm and reason among bands of Wisconsin Ojibwe. His leadership in word and deed prevented violence that could have instantly turned even sympathetic whites against the Ojibwe cause.

It is only at this point--after so many years of struggle--that Chief Buffalo's famous trip to Washington took place. After months with no response to Buffalo's letter, Ojibwe leaders decided to send one final delegation to negotiate directly with the "Great Father." This time, the 93-year-old chief himself was chosen to lead it. Oshogay, a talented orator also from the La Pointe band, came as the chief's primary spokesman. Their list of demands now included removing Watrous from office, remuneration for the deaths at Sandy Lake, the return of annuity payments to La Pointe, and the establishment of reservations where the Ojibwe had villages.

Etching of the 1852 Delegation to Washington, printed in Benjamin Armstrong's Early Life Among the Indians (1892). Chief Buffalo is almost certainly one of them, but we do not know which one. Armstrong himself, who was Buffalo's son-in-law and the interpreter for the trip, is presumably the white man depicted. The original photograph from which this etching derives is lost, but it likely identified each man. Despite claims in favor of other photographs, paintings, and sculptures, Leon Filipczak has shown on his blog Chequamegon History that, in fact, this etching remains the only image in which the great chief is (probably) depicted.

The Legacy of Chief Buffalo's Journey

The trials and tribulations of the chief's journey to Washington in 1852 are themselves quite a story, and one you will be able explore in CVM's new exhibit Changing Currents after its Grand Opening on December 7. As for the results of Buffalo's journey, scholars have recently called into question whether President Fillmore agreed to even a single one of the Ojibwe demands!

However, whether or not Buffalo was immediately successful in achieving his political goals is really beside the point. Despite being turned back multiple times on the journey, the persistent delegation was able to present its case before the President of the United States. For the second time, Ojibwe leaders from the Great Lakes had successfully bypassed the colonial chain of command American officials wanted them to use, and instead negotiated on their own behalf at the highest level of American government.

Chief Buffalo's legacy still holds true. Due in large part to his steady leadership, annuity payments returned to Madeline Island in 1853, and the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe provided the Ojibwe of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota reservations on their homelands. The reservations at Lac Courte Oreilles and Lac du Flambeau were two of the nine reservations established under this treaty. Chief Buffalo was still alive to sign it, and his name appears first among the 85 Ojibwe signators. Had the elderly chief died before his time--and leadership passed to another chief or been dispersed more widely among different bands--would violence have been avoided at that critical moment in 1851? It is impossible to know.

The image of Kechewaishke--Great Buffalo--quintessential Ojibwe chief, shaking hands and smoking a special Calumet pipe with the President of the United States remains an iconic moment in the collective memory of Wisconsin Ojibwe. It should be remembered as an iconic moment in Chippewa Valley and Wisconsin history, too, as a prime example of determination, peaceful protest, and cultural survival from an era in which such examples are all too rare.

You can learn more about treaties (including the U.S. treaty with the Dakota that ceded the lower Chippewa Valley), Ojibwe reservations, and other encounters between native Chippewa Valley residents and non-native settlers in Changing Currents: Reinventing the Chippewa Valley after the exhibit's Grand Opening December 7.

Changing Currents: Reinventing the Chippewa Valley has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the human endeavor. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, grant number MA-04-12-0089.

Sources

If you want to learn more about this fascinating era of Chippewa Valley history, check out these sources. (Full citations for this article available upon request.)

Armstrong, Benjamin. Early Life among the Indians. Ashland, Wis.: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892.

Filipczak, Leon. Chequamegon History blog. Available online here. Accessed 2014. [Filipczak's blog is a great source for current research on Wisconsin's Ojibwe, among other things. He is continually unearthing forgotten primary documents and providing great insights into the history of northern Wisconsin before 1860.]

"Minnesota Items." St. Paul Pioneer reprinted in the New-York Daily Tribune, 16 Dec 1850. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress. Available online here.

Miscellaneous Documents: 30th Congress, 1st Session - 49th Congress, 1st Session, 1849. Google Book. Available online here.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013.

Satz, Ronald. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin's Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States, Volume 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Company, 1851. Available as a Google Book here.

White, Bruce. "The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850," in McClurken, James M. et al., Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights, James M. McClurken, Compiler. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2000.

Send this blog post to someone:

SUBMIT